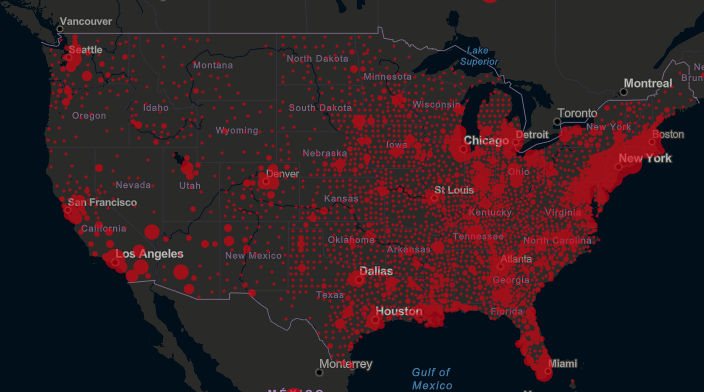

WHAT IS COVID-19 & WHERE WE ARE !

Consider the ways corona virus has unspoiled our norms and traditions. Who could have imagined drive-by birthday celebrations or virtual commencement ceremonies? Not long ago, few of us thought twice about reserving a cozy booth at a favorite eatery or reveling shoulder to shoulder at a concert venue.

Think you know everything there is to know about this viral menace? Take our quiz to see if you’ve been paying close attention—and good luck!

I walked up to City Hall in Philadelphia for the first scheduled protest in my city mourning the loss of George Floyd, who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. The streets were quiet due to COVID-19, but a small group of organizers set up in Dilworth Park—typically a space for interactive family fun.

The threat of corona virus is a major concern for protesters throughout the country, and many adjusted their plans to address the possibility of transmission. Here in Philadelphia, volunteers drew X’s on the ground for people to use as guides so they could stay at least six feet apart. The demonstration included a food bank, and volunteers handed out disposable masks and water.

Speakers used a megaphone so those far from the crowd could still hear stories and participate in chants. As we marched to the Museum of Art for the second scheduled gathering of the day, most people staggered their pace to avoid close contact. The sprawling lawns, wide sidewalk, and car-free parkway in front of the museum offered ample space to practice guidelines.

“Fortunately, many protesters appear to be wearing masks and attempting to be physically distanced, although risk probably increases any time protesters are congregating in large crowds.” Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, tells Health.

(After the protest in the park, I reached out to Rasmussen to find out if she's been seeing protesters adhere to pandemic guidelines.) “COVID-19 is a concern at any mass gatherings, including protests, because it can be spread by pre symptomatic or asymptomatic patients,” she notes.

As a journalist, it was challenging to interview participants while maintaining a safe distance—and no one there seemed unhealthy, so the virus was easy to forget. Amid the chaos of police clashing later in the day, it became impossible for me to even try to follow recommendations. When I realized that my physical safety was being threatened, my body forgot all about invisible threats.

Although no amount of planning will guarantee health and safety, these careful considerations from medical professionals can alleviate the stress of not knowing what will happen once protesters hit the streets.

Just because you're at a protest doesn't mean you should stop wearing a mask (and bringing a spare), carrying hand sanitizer, and practicing good hand hygiene, says Rasmussen. And anyone who shows COVID-19 symptoms, believes they have been exposed to the virus, is currently recovering from it, or is high-risk, isolate at home.

“Support the protesters in other ways—donating to bail/legal defense funds/mutual aid groups, amplifying important messages online, and more," says Rasmussen. "They should not attend a protest or any other type of gathering.”

Erik Jervis, a New Jersey-based trauma-focused therapist, tells Health that he's concerned by protesters who have experienced direct trauma or witnessed trauma at protests. Even if you haven't been physically harmed at these events, seeing others being harmed or hearing their screams can still cause emotional distress.

“Ask yourself if you’re mentally and emotionally prepared to [be involved in or] witness confrontations,” advises Jervis. People with PTSD, anxiety, or trauma in their history could be triggered, he notes—even if they haven’t dealt with symptoms for many years.

“If you’re feeling wound up or anxious, be present and take a step back,” says Jervis. “Get away from it for a moment. Walking away from the march isn’t a negative thing. You can always rejoin when you’re ready.” It's important to get support before, during, and after these experiences, he adds.

A medic I encountered (who prefers to stay anonymous) suggests thinking about how well your body tolerates heat, long bouts of standing, potentially walking for miles, as well as physical and emotional stress.

Pappadakis adds that protesters should reflect on their pre-existing conditions—even if they’re typically asymptomatic. Those who have COPD or asthma have a lower risk tolerance for irritants.

Finally, don't forget emergency medications—like inhalers and Epi-Pens—but also prescriptions you take regularly, in case of arrest or you're stuck in a location for longer than planned.

After I was exposed to tear gas, the skin around my hairline blistered for days because I wasn’t able to rinse it out of that area quickly enough. Pappadakis explains that skin irritations are a normal tear gas effect, and he also notes that vomiting and diarrhea can occur if the chemical is accidentally ingested.

“Both pepper spray and tear gas have a similar symptom presentation in patients. We’re usually worried about the eyes and lungs,” says Pappadakis. Eyes can swell or look similar to pink eye. Exposure can also cause wheezing, shortness of breath, and prolonged coughing.

Using a mask that seals tightly to the face with no gaps will help prevent these effects, he says. Because some people with asthma or breathing issues experience discomfort when wearing tight masks, they need to consider if it's wise to attend.

If you don't have a mask that seals up tightly, Pappadakis suggests pairing the mask you do have (which you should be wearing to protect against coronavirus anyway) with goggles to protect the eyes and lungs from tear gas.

If all you have is a cloth facial covering, put that on; it's better than nothing. Opt for long sleeves and long pants to protect the skin from exposure. He warns against wearing contacts; glasses are safer.

Protests can turn violent, so Pappadakis recommends carrying compression bandages and alcohol for cleaning wounds. Bring supplies for splints for ankles, legs, and joints in case of sprains or breaks.

Bumps and bruises happen, but people with increasing pain could have organ damage and should be seen at an ER, says Pappadakis. Concussions are another risk; if you get hit in the head and think you could have a concussion, seek medical attention ASAP.

It could lead to something more serious, like a brain hemorrhage. As the co-chair of a grassroots activism group that advocates for equitable access to quality emergency medical care, Pappadakis wants to highlight the importances of obtaining emergency care if needed. Know where the nearest ER or urgent care is and go if needed.

When I arrive on location, I scan the crowd for people I might need in an emergency. Medics often wear a red duct-taped medical cross symbol on their backpack and sleeves. These people will have the equipment and communication tools to get more help even if they aren’t formally trained.

In Philadelphia, some also carry glucose for diabetics and Epi-Pens for those who might have allergic reactions. Other volunteers, such as those handing out masks, hygiene kits, snacks, and bottled water are good to find, too. Keeping a mental tab of who these people are and what they’re wearing every day helps me find them when I need them.

Consider the ways corona virus has unspoiled our norms and traditions. Who could have imagined drive-by birthday celebrations or virtual commencement ceremonies? Not long ago, few of us thought twice about reserving a cozy booth at a favorite eatery or reveling shoulder to shoulder at a concert venue.

Think you know everything there is to know about this viral menace? Take our quiz to see if you’ve been paying close attention—and good luck!

I walked up to City Hall in Philadelphia for the first scheduled protest in my city mourning the loss of George Floyd, who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. The streets were quiet due to COVID-19, but a small group of organizers set up in Dilworth Park—typically a space for interactive family fun.

The threat of corona virus is a major concern for protesters throughout the country, and many adjusted their plans to address the possibility of transmission. Here in Philadelphia, volunteers drew X’s on the ground for people to use as guides so they could stay at least six feet apart. The demonstration included a food bank, and volunteers handed out disposable masks and water.

Speakers used a megaphone so those far from the crowd could still hear stories and participate in chants. As we marched to the Museum of Art for the second scheduled gathering of the day, most people staggered their pace to avoid close contact. The sprawling lawns, wide sidewalk, and car-free parkway in front of the museum offered ample space to practice guidelines.

“Fortunately, many protesters appear to be wearing masks and attempting to be physically distanced, although risk probably increases any time protesters are congregating in large crowds.” Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, tells Health.

(After the protest in the park, I reached out to Rasmussen to find out if she's been seeing protesters adhere to pandemic guidelines.) “COVID-19 is a concern at any mass gatherings, including protests, because it can be spread by pre symptomatic or asymptomatic patients,” she notes.

As a journalist, it was challenging to interview participants while maintaining a safe distance—and no one there seemed unhealthy, so the virus was easy to forget. Amid the chaos of police clashing later in the day, it became impossible for me to even try to follow recommendations. When I realized that my physical safety was being threatened, my body forgot all about invisible threats.

Although no amount of planning will guarantee health and safety, these careful considerations from medical professionals can alleviate the stress of not knowing what will happen once protesters hit the streets.

Just because you're at a protest doesn't mean you should stop wearing a mask (and bringing a spare), carrying hand sanitizer, and practicing good hand hygiene, says Rasmussen. And anyone who shows COVID-19 symptoms, believes they have been exposed to the virus, is currently recovering from it, or is high-risk, isolate at home.

“Support the protesters in other ways—donating to bail/legal defense funds/mutual aid groups, amplifying important messages online, and more," says Rasmussen. "They should not attend a protest or any other type of gathering.”

Erik Jervis, a New Jersey-based trauma-focused therapist, tells Health that he's concerned by protesters who have experienced direct trauma or witnessed trauma at protests. Even if you haven't been physically harmed at these events, seeing others being harmed or hearing their screams can still cause emotional distress.

“Ask yourself if you’re mentally and emotionally prepared to [be involved in or] witness confrontations,” advises Jervis. People with PTSD, anxiety, or trauma in their history could be triggered, he notes—even if they haven’t dealt with symptoms for many years.

“If you’re feeling wound up or anxious, be present and take a step back,” says Jervis. “Get away from it for a moment. Walking away from the march isn’t a negative thing. You can always rejoin when you’re ready.” It's important to get support before, during, and after these experiences, he adds.

A medic I encountered (who prefers to stay anonymous) suggests thinking about how well your body tolerates heat, long bouts of standing, potentially walking for miles, as well as physical and emotional stress.

Pappadakis adds that protesters should reflect on their pre-existing conditions—even if they’re typically asymptomatic. Those who have COPD or asthma have a lower risk tolerance for irritants.

Finally, don't forget emergency medications—like inhalers and Epi-Pens—but also prescriptions you take regularly, in case of arrest or you're stuck in a location for longer than planned.

After I was exposed to tear gas, the skin around my hairline blistered for days because I wasn’t able to rinse it out of that area quickly enough. Pappadakis explains that skin irritations are a normal tear gas effect, and he also notes that vomiting and diarrhea can occur if the chemical is accidentally ingested.

“Both pepper spray and tear gas have a similar symptom presentation in patients. We’re usually worried about the eyes and lungs,” says Pappadakis. Eyes can swell or look similar to pink eye. Exposure can also cause wheezing, shortness of breath, and prolonged coughing.

Using a mask that seals tightly to the face with no gaps will help prevent these effects, he says. Because some people with asthma or breathing issues experience discomfort when wearing tight masks, they need to consider if it's wise to attend.

If you don't have a mask that seals up tightly, Pappadakis suggests pairing the mask you do have (which you should be wearing to protect against coronavirus anyway) with goggles to protect the eyes and lungs from tear gas.

If all you have is a cloth facial covering, put that on; it's better than nothing. Opt for long sleeves and long pants to protect the skin from exposure. He warns against wearing contacts; glasses are safer.

Protests can turn violent, so Pappadakis recommends carrying compression bandages and alcohol for cleaning wounds. Bring supplies for splints for ankles, legs, and joints in case of sprains or breaks.

Bumps and bruises happen, but people with increasing pain could have organ damage and should be seen at an ER, says Pappadakis. Concussions are another risk; if you get hit in the head and think you could have a concussion, seek medical attention ASAP.

It could lead to something more serious, like a brain hemorrhage. As the co-chair of a grassroots activism group that advocates for equitable access to quality emergency medical care, Pappadakis wants to highlight the importances of obtaining emergency care if needed. Know where the nearest ER or urgent care is and go if needed.

When I arrive on location, I scan the crowd for people I might need in an emergency. Medics often wear a red duct-taped medical cross symbol on their backpack and sleeves. These people will have the equipment and communication tools to get more help even if they aren’t formally trained.

In Philadelphia, some also carry glucose for diabetics and Epi-Pens for those who might have allergic reactions. Other volunteers, such as those handing out masks, hygiene kits, snacks, and bottled water are good to find, too. Keeping a mental tab of who these people are and what they’re wearing every day helps me find them when I need them.